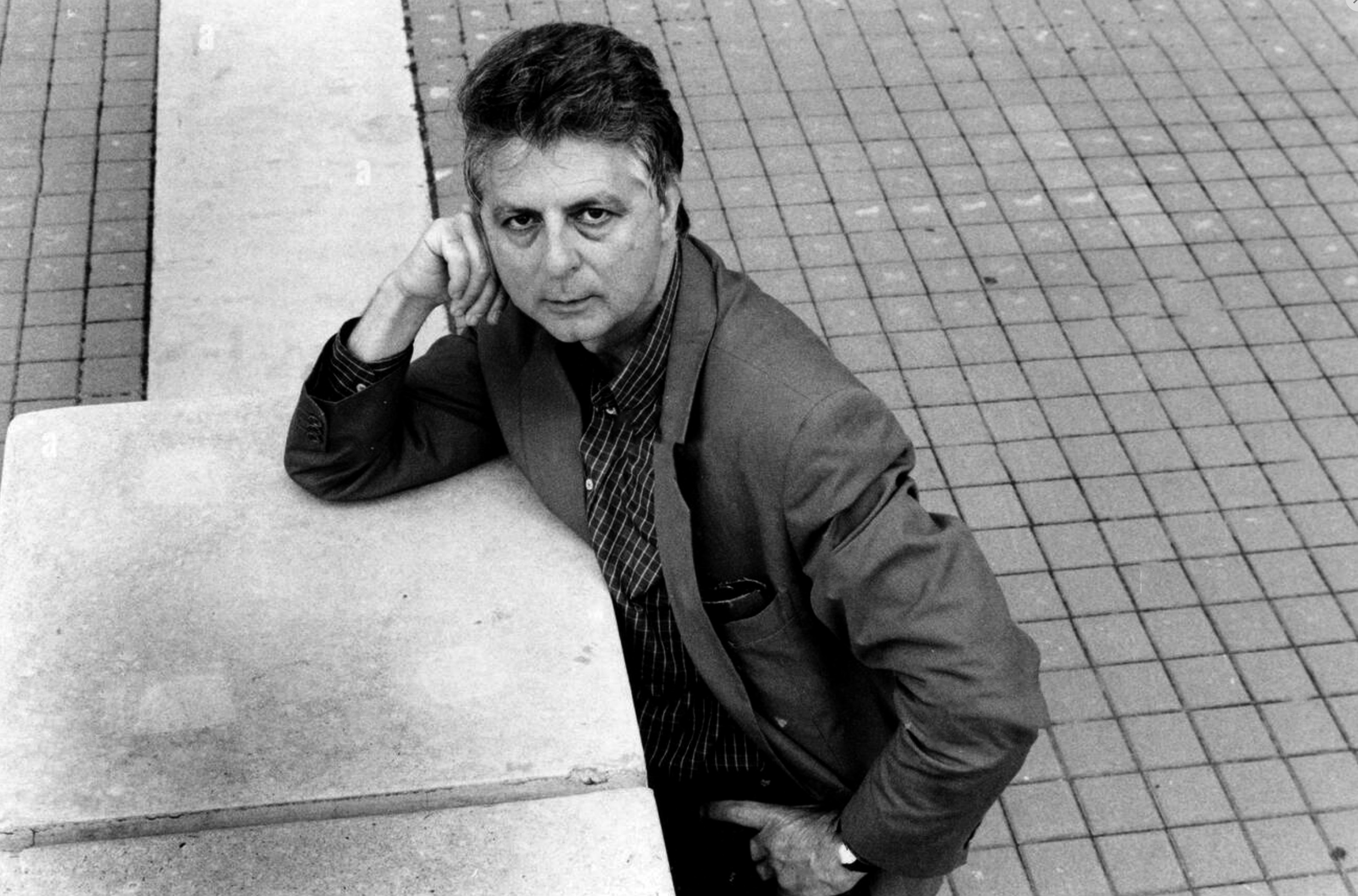

Alfonso Berardinelli is an Italian critic and essayist belonging to a category that once had great wealth, but which today has only a few rare representatives: literary criticism, which maintains a consubstantial relationship with cultural criticism. Contemporary Italian literature, especially poetry, the genre to which Berardinelli devoted himself almost exclusively, has been subject to his wide-ranging critical discourse, so often the subject of strong polemics. Satire and controversy are, moreover, discursive genres that he has cultivated, almost as a programme necessarily inscribed in the exercise of criticism. It is impossible to trace a panorama of Italian poetry since the middle of the last century, and transformations in the modes of reception and dissemination of literature in the public space, without taking into account the enormous and persistent activity of this exemplary critic.

This interview with Alfonso Berardinelli, the most important Italian literary and cultural critic, who has been active for more than half a century, is not only an approach to the critical-theoretical ideas of this ‘invisible writer’, but also a cultural diagnosis of our time.

ANTÓNIO GUERREIRO Your work encompasses poetry (which you abandoned early), essays, literary criticism and cultural criticism, just to mention the essential. In your intellectual career how did you transition between these genres? Even though for almost fifty years you have been visible in literary and cultural life, including outside of Italy, in a collective book dedicated to you, you’re described as the ‘invisible writer’. In this characterisation, should we stress the ‘writer’ or the ‘invisible’?

ALFONSO BERARDINELLI Maybe my work, if it is in fact a work, is not too varied or plural. At least that’s my impression. I have always written according to the circumstances, the immediate necessities and the requests that I received. I believe that’s also why I like to be interviewed! It transports me to my literary genre: the essay, the dialogue with other texts. Even if they vary in size, all my texts are essays, including my newspaper articles. Giacomo Leopardi, whom in Italy we consider the greatest poet after Dante, our classic of modernity, once said in a letter that nothing he had written were ‘works’, but only attempts, trials, essays. I have worked in journalism in a continuous manner for the last twenty years, for economic reasons, since I had no other source of income. Before that, especially in the 1980s, when Piergiorgio Bellocchio and I created the ‘personal magazine’ Diario, which only came out when we had something to say (twelve issues in ten years), I criticised journalism and newspapers. But now magazines are a cultural medium that has almost completely disappeared and newspapers contain endless pages dedicated to books and ideas. The journalistic feuilleton replaced the magazine. Today, given the enormous power of the Internet, printed newspapers are kind of a noble anachronism and their readers something akin to an elite, doomed to extinction in the near future, I believe. I like to write articles in newspapers because this way I feel like I’m in a past time, almost in the Enlightenment era of the 18th century (I write my articles by hand and then dictate them). In fact, the 18th century (my favourite) was precisely that of the essay, mixed genres (including the epistolary genre), philosophy, autobiography, pamphlets.

If my work seems plural that might be because, of all the genres, the essay is the most open and varied. There are no precise rules, except that you can’t make things up. It’s the most experimental and protean of all the genres. Obviously, I’m not referring to the vast academic and specialised production that is now written by scholars and professors: for the most part, monothematic books with countless footnotes and endless bibliographies. The essay dispenses with endnotes and professional bibliographies. It’s not systematic ‘research’ funded by public institutions. It’s always a personal, subjective, occasional, improvised, reactive, dialogic, controversial question… As time went by, I realised that I was less of a literary critic and more of a cultural and social critic, in a style that approached digression and satire. Historically, satire preceded and announced what, following the Enlightenment and the advent of Marxism, would become known as the ‘critique of ideology’. But the latter presupposed a social theory. Satire doesn’t need theories. It can limit itself to the confrontation with the worst and the best. Satire, a sense of humour, these are pretty detoxifying, they have a purifying role, they disseminate a sense of ridicule… And today culture needs this, since it suffers from an intoxicating superproduction.

The problem with today’s culture is that it doesn’t tolerate the existence of criticism. Political satire is extensively disseminated whereas cultural satire doesn’t exist. I say this because I feel that I serve almost a public role. Nonetheless, in reality I feel like an ‘invisible writer’ and I am one. Invisible in two senses and for two reasons. Firstly, because I never go on television, which is what allows almost anyone to publish the novel of their lives or their seasonal bestseller. Secondly, because I don’t hold any public office: I’m not president, director, professor emeritus, scholar, etc. I only have my first name and surname. ‘Invisible writer’ also because essays are not considered ‘creative’ literature. In my opinion, however, criticism is also a literary genre. It’s the genre of interpretation and judgment. I usually say that criticism resembles the endocrine system: it’s not every visible, but when it isn’t working properly all the other literary systems or genres suffer; they become deformed, put on weight, shrink, lose balance…

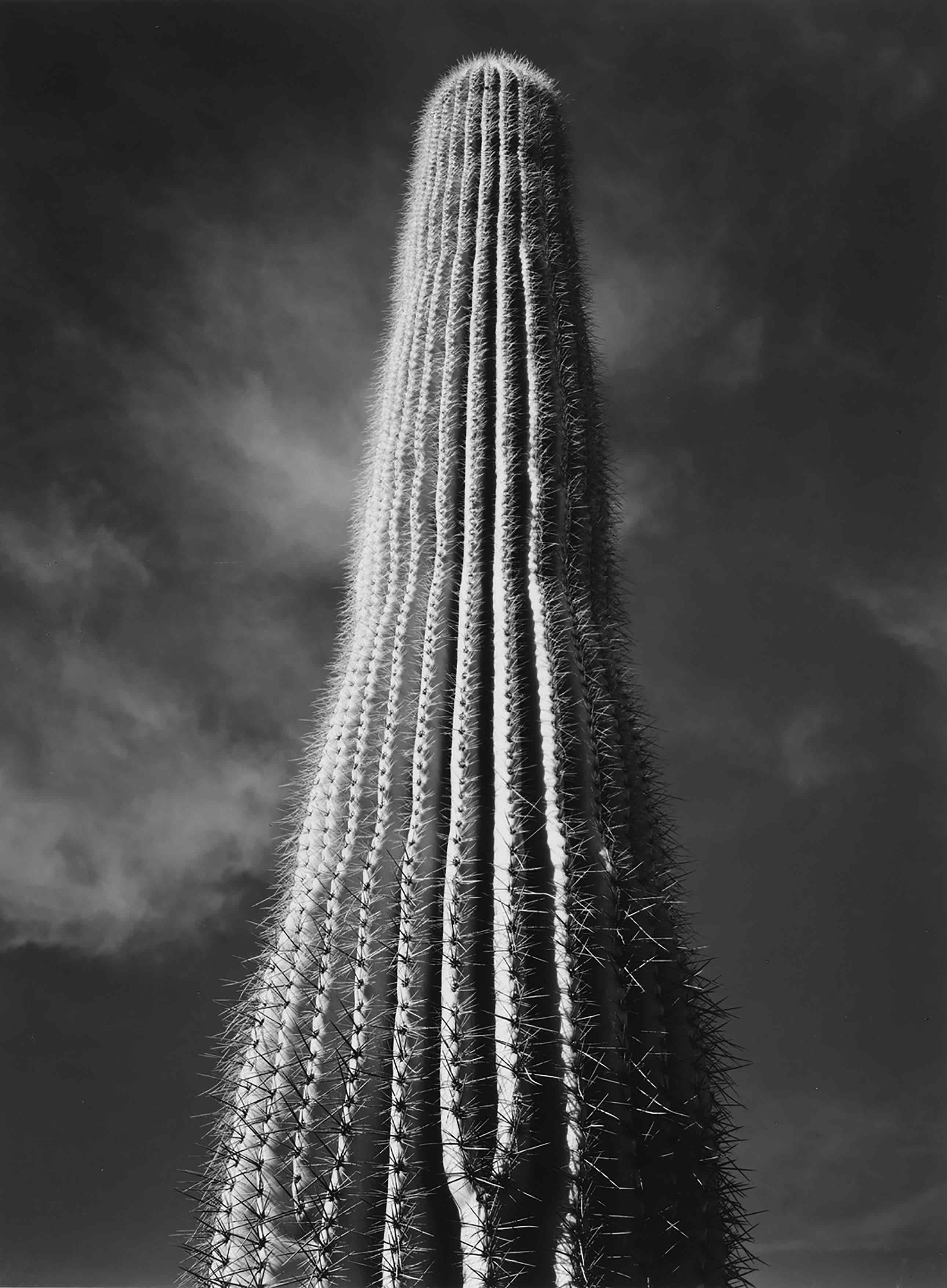

Ansel Adams, Saguaro Cactus, Sunrise, Arizona, 1946 © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

"Mass culture entered and conquered universities: one of the most obvious symptoms was the Umberto Eco phenomenon with his incredible success, both among mainstream readers and university professors."

AG L’eroe che pensa [The Hero Who Thinks, the title of one of his books], as you describe the figure of the intellectual, could just as easily describe you. Nonetheless, it is about the end of this figure that you write in one of the chapters of your book. Do you believe that you belong to an almost extinct ‘species’, which therefore occupies a critical role (in the sense that it is affected by the ‘crisis’), amplified by a hyperconsciousness of its situation within its own era?

AB That’s right. For me, it’s enough to ‘exemplify’ another way of being that has always characterised the Western cultural tradition. I’m only a modest and small ‘epigone’ of this tradition, of course. The intellectual as a hero, a character who thinks more than he acts, who thinks before he acts to the point of not acting, or of acting with reluctance and scepticism, was a literary figure: Hamlet, Alceste, Andrei Bolkonsky, and also Ivan Karamazov, who judges his father but doesn’t kill him and falls into a kind of madness when he realises that a murder was committed to implement his idea. I chose to use the expression ‘hero who thinks’, since today the term ‘intellectual’ is dull, it has become worn out and abstract. Its meaning is too sociological: it indicates a social category more than it does individuals. On the contrary, I wanted to highlight that the intellectual is above all a particular individual, with his experiences, reasons, character and way of expressing himself. And he’s personally risking something. Often the hero who thinks can’t stand the category of the intellectuals, their ‘spirit of unity’, their class patriotism. In this sense, he occupies a critical social position, i.e. unstable, variable, risky, not bureaucratically guaranteed. I dislike having institutional authority, in fact, it irks me. I’m satisfied with being read and understood. Not read by many, but by those who take an interest and are able to understand what I say. The authors of bestsellers don’t have this small privilege. Their readers are a ‘mass’, not individuals.

"A minha geração, que tinha vinte anos em 1968, que parecia hipercrítica e até revolucionária, a partir de 1980 transformou-se numa classe média mais interessada em conservar a sua hegemonia do que em transformar a sociedade."

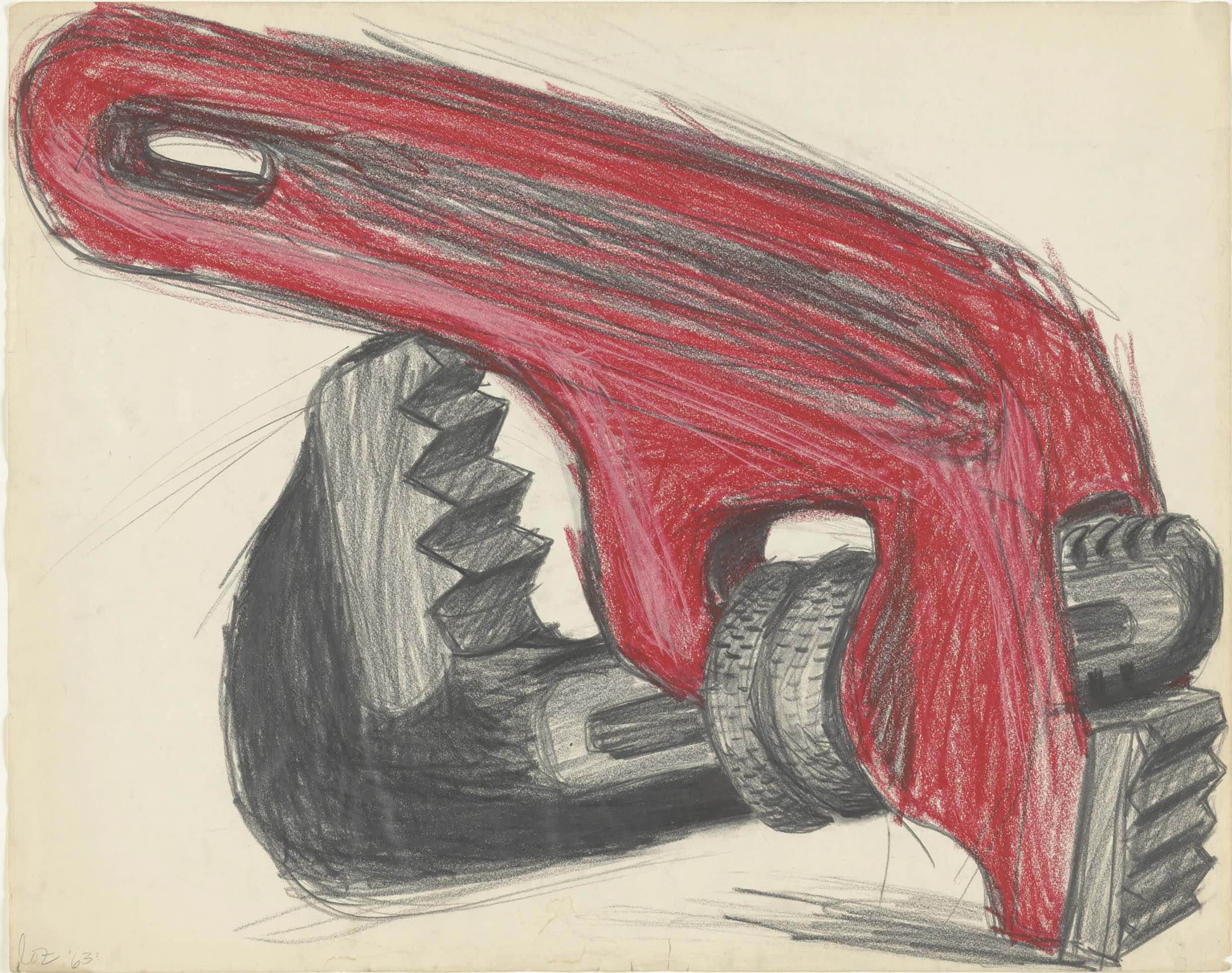

Lee Lozano, Untitled (Tool), 1963 © Estate of Lee Lozano

AG "My generation, which was twenty years old in 1968 and which seemed hypercritical and even ‘revolutionary’, from 1980 onwards turned into a middle class more interested in preserving its hegemony than in transforming society."

AB The reasons are many and I’m not sure I can identify them all. Between 1970 and 1980 the distribution of the social classes changed, therefore the relationship between culture and society, between high culture and mass culture also changed. Mass culture entered and conquered universities: one of the most obvious symptoms was the Umberto Eco phenomenon with his incredible success, both among mainstream readers (who understand him and don’t understand him, but still fall for his erudite exhibitionism) and university professors, who took him as a role model and dreamed more frequently of becoming something like him… So-called ‘high culture’ or ‘elite culture’ didn’t react to the literary and cultural mediocrity that was The Name of the Rose. I don’t think there is any real writer in this world who appreciates Eco’s novels. Yet, they kept quiet. I mention this episode for the sake of simplicity, since it can be seen as one of the many symptoms of that extinction. Both from a social and cultural point of view, this phenomenon was clearly described from several perspectives, both by Pasolini in his last ‘corsair’ articles, and Enzensberger, who described the wave of a new, vaster and more influential ‘petite bourgeoisie’, which has become a universal middle class. This new class has taken over literature, the arts and universities (there’s almost nothing left outside of universities), occupying three quarters of society and gaining control of the cultural hegemony that was held by those who possess the great economic powers. The dominant culture, according to Pasolini and Enzensberger, has become the culture in constant metamorphosis of this socially central class. Previously, the critique of dominant society and culture was part of class struggle and political conflict. Critique was born from a theory, and that theory was Marxism, which saw the historical dynamics as a struggle between capital and the working class. But the latter, following technical-economic development, completely disappeared. The factory worker became the petit bourgeois, as had been foreseen in the 19th century by Marx’s most intelligent opponent, the Russian liberal-socialist Aleksander Herzen. My generation, the one which was twenty years old in 1968 and which seemed hypercritical and even ‘revolutionary’, from 1980 onwards turned into a culturally hegemonic middle class, i.e. more interested in preserving its hegemony than in transforming society. This is how critique has gradually disappeared. All culture is in the hands of this vast and multiform class that uses it as self-confirmation and self-promotion. Today, culture is ‘by definition’ an object that doesn’t allow criticism. Therefore, you can only criticise it if you’re a particular individual, somewhat antisocial, anachronistic and ‘without ambitions’. This is the reason why when Piergiorgio Bellocchio and I founded the Diario magazine in 1985, in the first issue we decided to publish not Marx, but Kierkegaard, the philosopher who theorised the category of the ‘individual’ and expressed himself, above all, not in the form of a theoretical treatise, but of a diary… Our magazine-diary was entirely written by the two of us. And our public was composed of very particular readers, hidden under the surface of society. Readers who wrote many letters to us, messages in a bottle that sprung from their loneliness. Enzensberger told us that even in Germany we had ‘a few fervent readers’…

[...]

Share article