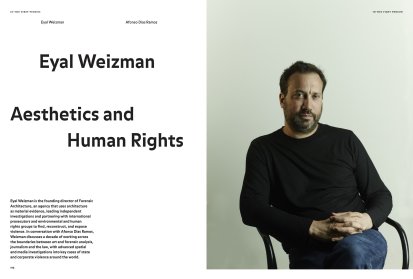

Eyal Weizman is a British Israeli architect born in Haifa. He is the founding director of Forensic Architecture and the Professor of Spatial and Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he founded the Centre for Research Architecture. He sits on the board of the International Criminal Court and has been appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire for services to architecture. Weizman first came to public prominence when he curated, with Rafi Segal, a showcase of Israeli architecture at the International Union of Architects Congress in Berlin, in 2002, in which they decided to present settlements. The Israel Association of United Architects withdrew their support, cancelled the exhibition and destroyed the catalogues. This move and the ensuing controversy won him worldwide attention. Since 2003, he has been leading a new approach to architecture, scanning the built environment for clues about the crimes perpetrated there, with books such as Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (2007), The Least of All Possible Evils (2011), or The Conflict Shoreline (2015, with Fazal Sheikh). When Weizman looks out at urban landscapes such as the West Bank, as in the Al Jazeera film The Architecture of Violence (2014), he sees a battlefield. ‘The weapons and ammunitions are very simple elements: they are trees, they are terraces, they are houses.’ That is why, in 2010, he founded Forensic Architecture, an agency that has developed pioneering methods for spatial investigations of state and corporate violations, with an interdisciplinary team of architects, filmmakers, journalists, coders, archaeologists, lawyers, and scientists. They develop advanced media and spatial research with and on behalf of legal teams, human rights organisations, environmental justice groups, and communities affected by state violence, dealing with topics that range from the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean to the secret torture camps in Cameroon, from chemical attacks on civilians in Syria to CIA drone strikes in Pakistan or the enforced disappearance of students in Mexico. Using a vast range of investigative methods – from the ultrasophisticated methods of machine learning, computer vision, artificial intelligence and remote sensing, to cartographic regression and cloud studies by painters and art historians – to expose atrocities, environmental crimes, cultural heritage issues and individual killings, they have provided decisive evidence in national and international courts, as well as citizen tribunals and human rights processes, leading to military, parliamentary, and UN inquiries. These investigations translate into media installations and audiovisual representations in very high demand by the most disparate forums: from courtrooms and parliaments to museums, web platforms, and mainstream media outlets. Forensic Architecture has held major art exhibitions in documenta 14, Venice Biennial, the Whitney Biennial, the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA) and the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, and it was also nominated for the Turner Prize. In addition to countless distinctions across the fields of human rights and technology, this collective has also won an Emmy and a Peabody Award. With architecture now winning the most prestigious awards in journalism today, the built environment finds itself increasingly called to the witness stand. The Israeli, American and British militaries have been setting up architectural academies for soldiers, and think tanks and universities around the world are opening new digital investigative units to collect, store, and analyse data from geopolitical conflicts. In this video conference interview, Eyal Weizman looks at the new era of human rights and war crimes investigations, in which architectural intelligence will be increasingly called upon.

Eyal Weizman is the founding director of Forensic Architecture, an agency that uses architecture as material evidence, leading independent investigations and partnering with international prosecutors and environmental and human rights groups to find, reconstruct, and expose violence. In conversation with Afonso Dias Ramos, Weizman discusses a decade of working across the boundaries between art and forensic analysis, journalism and the law, with advanced spatial and media investigations into key cases of state and corporate violence around the world.

© Paul Stuart

AFONSO DIAS RAMOS Tell us a bit about your background. What has shaped your understanding of architecture as political work? How did you come to focus on the interaction of violence with the built environment?

EYAL WEIZMAN I had two competing interests as a young person. One was shaped by a certain interest in theory, particularly political theory, through the reading groups I was part of in Haifa, run by the Communist Party that had a headquarters there. This group of Palestinian, Israeli and Jewish intellectuals was trying to build a common understanding of the material realities of settler colonialism. Haifa is an interesting place in this sense, because the city still has a surviving Palestinian population. While most other major cities in Palestine were ethnically cleansed in 1948, in Haifa, some of the population survived in the urban culture of what became the Israeli state, rather than in the rural cultures that are wrongly associated with the expulsions of the Nakba.

"No space is ever static. Force and form are related through acts of violence."

The other interest I had was a spatial one, and it was also shaped by Haifa. Growing up there, one saw geography and topography operating as mechanisms of separation, as components of the Israeli spatial apartheid. Palestinian neighbourhoods were clearly circumscribed. They were legally but not socially porous. The Palestinian communities in the valleys had Jewish neighborhoods piling up above them in the hilltops of Haifa where I grew up, in a very middle- ‑class family, on Mount Carmel. I always wanted to be an architect and I wanted to do political theory. I was attracted to architecture as an aesthetic practice. In fact, I still keep sketchbooks with designs. However, I was looking for ways to connect those two things. When I became a young architecture student in London at a somewhat experimental school, the Architectural Association, I realised that what bound those two fields together was the study of the violence of transformative incidents, when political power and built space interact, sometimes with devastating consequences. The study of destruction and the study of construction then became related, as complementary moves in a political shaping of space. I understood politics as one of the most important formative forces in the re-organisation of space. Political theory and architecture were not unrelated, but mutually constitutive fields. Architecture is political force slowing into form. This idea is very important for me. It is about a reading of space that is an event. No space is ever static. Force and form are related through acts of violence. The violence that I had experienced in the context of Israeli settler colonialism was the 1948 destruction of Palestinian habitats, the destruction of refugee camps and cities in Gaza and the West Bank that still continues today, the bombing of Lebanon, and so on. I could see how politics actually manifested itself in acts of destruction but also in acts of construction, with the roads and the settlements on a territorial scale which operated as a means of domination, separation and extraction of Palestinian life from that space. I understood destruction and construction to be intimately related, as the means by which force acts on form. By looking at form, we can read force. Look at any physical reality, and not just in the context of war or Palestine. Take an architectural project. Where are the walls? Where are the doors? What is their size? Where are the borders? All this is a result of conflict. Sometimes it is articulated politely, sometimes with eruptive violence. Conflict shapes space through pulling and pushing. This is an understanding of architecture as a political plastic, and as an elastic medium. The disposition of material form is a diagram of the contradictions of force at a particular moment. It makes no sense to create big ontological separations between construction and destruction, or between the city and the countryside. The city shapes the countryside by cutting it apart. These are, again, mutually constitutive.

[...]

Share article