– Goooooooal! Goooooooal! Goooooooal!

This cry, almost onomatopoeic and infinitely reiterated, using all the possibilities of modern technology to augment its voice, volume, power and reach, continues to be heard everywhere. Today, this shout is almost always accompanied by animated omnipresent images.

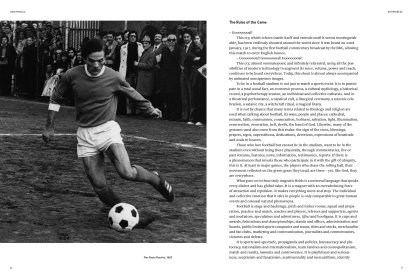

To be in a football stadium is not just to watch a sports event. It is to participate in a total social fact, an economic process, a cultural mythology, a historical record, a psychotherapy session, an individual and collective catharsis. And in a theatrical performance, a mystical cult, a liturgical ceremony, a totemic celebration, a satanic rite, a witchcraft ritual, a magical litany.

It is not by chance that many terms related to theology and religion are used when talking about football, its ways, people and places: cathedral, miracle, faith, communion, consecration, holiness, salvation, light, illumination, resurrection, veneration, hell, demons, the hand of God. Likewise, many of the gestures used also come from this realm: the sign of the cross, blessings, prayers, signs, superstitions, dedications, devotions, expressions of beatitude and nods to heaven.

Those who love football but cannot be in the stadium, want to be in the stadium even without being there physically, through commentaries, live or past streams, features, news, information, testimonies, reports. If there is a phenomenon that invests those who participate in it with the gift of ubiquity, this is it. At least in major games, the players who chase the rolling ball, their movement reflected on the green grass they tread, are there - yet, like God, they are everywhere.

What goes on in these truly magnetic fields is a universal language that speaks every dialect and has global value. It is a magnet with an overwhelming force of attraction and repulsion. It makes everything move and stop. The individual and collective emotion that it stirs in people is only comparable to great human events and colossal natural phenomena.

Football is stage and backstage, pitch and locker rooms, squad and preparation, practice and match, coaches and players, referees and supporters, agents and mediators, speculators and adventurers, tifosi and hooligans. It is cups and awards, federations and championships, stands and offices, administration and boards, public limited sports companies and teams, titles and stocks, merchandise and fan clubs, marketing and communication, journalists and commentators, victories and defeats.

It is sports and spectacle, propaganda and politics, bureaucracy and plutocracy, nationalism and internationalism, team fandom and cosmopolitanism, match and results, lawsuits and controversies. It is playfulness and seriousness, scepticism and fanaticism, sentimentality and mercantilism, identity (geographical, cultural, social and sexual) and transfer, the pass of the ball and the pass of the players, psychological whiplash and the dance of managers, the buying and selling. It is memory and expectation, concentration and exaltation, expansion and repression, preciseness and delirium, catharsis and sublimation, conviviality and violence.

Besides what it is, today football is also what is born and grows from it. Football is the unstoppable images on screens and the animated words that it generates in the mouths of those who talk about it round the clock – at home, at work, at the café and the barber’s; during lunch and dinner; before, during or after work or leisure; with their children and parents, uncles and cousins, male and female colleagues, friends and enemies.

To hear talk about football is to hear words that refer to techniques and tactics, aesthetics and eroticism, mathematics and statistics, music and ballet, probability and descriptive geometry, holiness and profanity, poetry and prose. To hear talk about football is also to hear the most ignorant and primitive words, the most useless and unnecessary, the most aphasic and improper – it is to suddenly come face to face with the most shameless and aggressive Kitsch.

Football gave rise to the largest and most extensive verbal industry that exists on Earth and under the sky. With football as a topic, motif, inspiration or pretext, people talk, pontificate, give speeches, discuss, ramble, speculate, ponder, debate, deduce, comment, reason, plot, predict, agree, conclude, assume, foresee, infer, disagree, argue, recriminate, accuse, defend, insult, theorise.

As in love (The Metaphysics of Love, Schopenhauer), there is also a metaphysics of football, which asks questions about what lies beyond the physical and searches for the immobile driver, the founding principle, the primary cause, the ultimate finality, the relationship between mind and matter, substance and attribute, contingence and necessity, absolute and relative, permanence and change, free will and possibility, reality and image, being and entity, immanence and transcendence, space and time.

Alongside a metaphysics, football also has an epistemology. It is marked by a copious and prolix discourse on the method used and a dispute between belief and truth, hypothesis and model, experience and certainty, theory and evidence, event and language, law and exception, deduction and induction, verifiability and falsifiability, conjecture and refutation, logic and meaning, rationalism and empiricism. Besides a metaphysics and epistemology, football, as a great phenomenal object, seems to require a phenomenology that appropriates what Husserl says in the Fifth Cartesian Meditation about the body, the self and the other.

To talk about football is to talk about an expanding universe with an exclusive big bang, a private space-time with its own theory of relativity. It is to talk about our current world and the time that makes this world what it is. It is to talk about a planetary, cosmic and universal phenomenon, which touches everyone, even those who prefer to remain detached, distant, aloof or evasive.

It is to talk about crowds, mobilisation, emotion, effusiveness, fusion. It is to talk about conviviality, connivance, fair play, confrontation, violence. It is to talk about idols, fetishes, mascots, alibis, totems, taboos. It is to talk about the most local and the most global, the most individual and the most collective, the most particular and the most general.

Norbert Elias was the author of the famous The Civilising Process and his disciple Eric Dunning applied Elias’s theory to the development and metamorphosis of modern sports and its increasing violence. In Quest for Excitement, a seminal book that reflects on these topics and issues, master and disciple accurately examine sport practices, including football, as indicators of what goes on within society as a whole, seeing the ‘quest for excitement’ as one of the essential phenomena of our current civilisation.

To talk about football is to talk about the most divisive and the most aggregating, the most sectarian and the most unifying, the most differentiating and the most homogenising, the most excluding and the most representative. It is to talk about the most rational and the most irrational, the most urban and the most tribal, the most sophisticated and the most primitive. It is to talk about power, art, iconography. It is to talk about technique, industry and commerce. It is to talk about ‘interclassism’ and class conflict. It is to talk about epics, lyricism, dramaturgy, cinematography. It is to talk about concept and preconception. It is to talk about law and the law of the jungle. It is to talk about moralism and corruption. To talk about football is to talk about leisure and business. To talk about football is to talk about sports, entertainment, identity, culture, architecture, anthropology, sociology, law, psychology, economy, politics, communication.

In his classic work Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture, Johan Huizinga defends that play is a primordial instinct, representing one of the most original forces of pre-human and human history and one of the most deeply rooted. For this cultural historian, the homo ludens is the vertex of a triangle whose two other vertices consist of the homo sapiens and the homo faber. Huizinga believes that culture is born from play, in the form of rites, the sacred, language and poetry.

Play is logos (with its rationality and logic), ethos (with its rule and authority) and pathos (with its emotion and the empathy that it generates). Beneath numerous human activities – from law to science, from sports to art, from literature to politics – there is the play instinct. In play are founded the arts of expression and competition, the arts of thought and discourse, rhetoric and dialectic, with its expressions of accusation and defence, both in the political tribune and in the judicial court. It is in this primordial play that word games and love games find their first model. And it is also under this paradigmatic impulse that voluntary fighting games and forced war games take place.

According to Huizinga, play, with its instinct and seduction, is more primordial and primitive than culture, since it is one of the things that humans share with animals. As he states in the book: ‘Play is more ancient than culture itself, since the latter, even in its most rigorous definitions, always presupposes human society, but animals did not need humans to initiate them into ludic activity.’

This is why zoologists, ethologists and anthropologists have been studying this sport and have searched for the distant origins of football in the behaviour of animals and primitive tribes.

Everything related to football unleashes a game of adherence and rejection, attraction and repulsion. Its primitivism has a paradoxical effect. The rejection of football with its primary tribalism is often used by those who want to display intellectual sophistication as proof of their distinction. At other times, a love of football is displayed by intellectuals to prove that they belong to the human species, the people and their most common manifestations.

For some, football is a new and more insidious opium of the people, numbing and alienating. Jorge Luis Borges stated that ‘football is popular because stupidity is popular.’ And added: ‘Chess today is being replaced by football, which is a game for idiots, not for intellectuals.’ In King Lear, Shakespeare has a character exclaim: ‘You, base footballer.’ Echoing Clausewitz and Lenin, for George Orwell, football is the continuation of war by other means. But some defend that football is the main substitute for confrontations and conflicts.

For many, football is an art as creative as any other and a mode of popular culture with an unparalleled communal power of seduction. Pierre de Ronsard and Henry de Montherlant wrote poems to both the ball and the game. And Mário Cesariny, in his poem ‘Cake Shop’, has the following verses: ‘Isn’t it true, boy? And tomorrow there’s football / before the movies madame blanche and chit-chat.’

The writer Clarice Lispector wrote a delightful essay on her ‘impassioned ignorance about football’ and her desire to one day (maybe ‘when she’s an old lady who walks slowly’) learn about what she does not know, since football is part of and ‘represents life’. In this essay entitled ‘Armando Nogueira, Football and I, Poor Thing’, she recounts that she had only watched a game live in a stadium once. Since she could not understand what was happening on the pitch, she would ask questions to anyone accompanying her and would receive brief and irritated answers in return, having distracted those who only wanted to have their eyes and other sensory organs focused on the game. Clarice reveals that she would also ask one of her sons, when they sometimes watched football together at home on TV. His answer was equally brief and blunt, followed by the commentary: ‘You really don’t get this, mum, there’s no point.’

In Brazil, the stadium-country where football is everywhere and thrills everyone, many writers have written about matches, players and championships. The playwright, journalist and essayist Nelson Rodrigues is the most famous and renowned. Like Cecília Meireles (poem ‘Football’: ‘The lovely ball / rolls…’) or Manuel Bandeira (‘I have also participated in this collective delirium and since the beginning of the championship I have been glued to my radio listening to Brazil’s matches…’), the poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade also penned prose and poetry on the sport played with one’s feet.

The philosopher and novelist Albert Camus, who had been a goalkeeper on his college team, loved football and said that there was no place in the world where you could be happier than in a football stadium. He confessed that all he knew about human morality, about the duties and obligations of men towards each other, he owed to football. Jean-Paul Sartre, who first was Camus’s friend and later his enemy, spoke about the ‘eleven merging’ on the pitch, stating that in football everything was complicated by the simple presence of the opponent. In a rare lyrical-epic rapture, Vladimir Nabokov referred to the goalkeeper as the ‘lonely eagle, the mystery man, the last wall’.

Although the baron Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, said that ‘emulation is the essence of football’, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, in La Pensée sauvage, told the story of the Gahaku-Gama, from New Guinea. This people learned football from the missionaries, but when played by them and according to the moral and social values of their community, the game had as many parts as were necessary to strike a balance between those who won and those who lost. For the Gahaku-Gama, a football match was not a competition with winners and losers – it was a rite of balance, tie, solidarity and equality.

The famous British historian Eric Hobsbawm, who looked at the 20th century with a sharp and analytical mind, said that football was a sport that ‘had made its way through the world’, because it was ‘simple and elegant, unhampered by complex rules and equipment and which could be practiced on any more or less flat open space of the required size… making it truly universal’ (The Age of Extremes: History of the World, 1914–1991).

In the long history of football, simultaneously stable and varied, the current age is the era of football as spectacle and business: financial, media-oriented and technocratic. It is the football of billionaires and despots, stars and big names (see our dossier on ‘Fame’, in Electra 11).

For this reason, every father and mother wants to put their son in football school, in the hope that one day he will become a Messi, Ronaldo, Mourinho, Guardiola, Klopp, or at least a Beckham – meaning someone that is narcissistically beautiful, rich, famous and powerful.

The essayist Victor Cunha Rego, who has lived in many countries, including Brazil – which gave him a distilled and sometimes disenchanted experience of the world and those who inhabit it – wrote, at the end of the last century, in an article entitled ‘Virtual football’:

Share article