Not long after the last war, in a lecture on the ‘problems of regulation in the body and in society’, the great epistemologist Georges Canguilhem explained why the regulation of an organism should not be confused with the organisation of a human society. A living body is a self-regulating being, for whom ‘the norms or rules of its existence are indicated within its very existence’. In medicine, the problem to be addressed is disease not health, cataracts not good eyesight. When it comes to society, however, the troubles to be tackled – poverty, corruption, violence and more – are clear. What is less evident is the ideal we strive to attain, or, in other words, justice. Canguilhem writes:

Alain Supiot is a professor at the University of Nantes and the Collège de France. He is the author of La gouvernance par les nombres, 2015 [Governance by Numbers, The Making of a Legal Model of allegiance, 2017]. In this article he looks at the long history of governance by law up until the current system of government that is guided by quantification and by numbers – not only in economic terms but also in a social dimension. It is market globalisation and its immanent neoliberal principles that determine the hegemony of numbers in the information age.

There is no society without rules, yet in society, there is no self-regulation. There, regulation is always, if I may say so, something added on and always precarious (...) justice, the supreme regulation, does not appear in the form of an apparatus produced by society itself. Justice must come from elsewhere in society.

But where is that elsewhere that is sought by humble humans from their very first childhood quarrels and that is unquestioningly assumed to exist? In general terms, justice may be said to lie within an impartial, neutral third party. In early life, this third party takes the shape of a mother or father. To ensure that the disagreement between you and I does not descend into a fist-fight, we must be able to count on her or on him; we must be able to refer to a single law or a single judge using the same language. Throughout history, these third parties have taken multiple forms but they have all been characterised by religious or secular heteronomy. In other words, these third parties acting as guarantors of justice are the product of an act of faith in undemonstrable truths. It may be faith in a sacred book like the Bible, the Koran or the Vedas, or in what the United States Declaration of Independence terms ‘self-evident truths’. These truths are proclaimed in international declarations and national constitutions.

Like any normative system, the law in the West is founded on dogma; it is based on those undemonstrable truths being imposed equally upon us all. One example is the principle of equal human dignity, which has the force of legal truth, notwithstanding biological and sociological differences. Yet in the West, the law is also understood as a technique at the disposal of human beings, as the expression of their ability to set the rules governing their relations through conscious effort. This ideal of the rule of law was proudly advocated by the Greeks, with Plato stating that ‘the law reigned supreme over men instead of men being tyrants of the law’. For the Greeks, freedom was associated with a rule of law discussed collectively rather than with the possession of individual rights. This is why the rule of law went hand in hand with the invention of democracy. Democracy is a legally complex arrangement entailing the creation of ‘assemblies of words’ where members of a community (often limited to free men) gather on an equal footing. Jean-Pierre Vernant provided a wonderful description of these assemblies. The participants form a circle and a sceptre is placed in the centre (en méso, which also denotes milieu and measure) to symbolise power. Every individual is equally entitled to speak (isogoria). Anyone who wishes to comment on what is or what should be, steps forward and takes the sceptre. From that point on, they must no longer express their personal interests; instead, they must opine what they believe to be just and right for the city as a whole. When they have finished, they return the sceptre to the middle and resume their role as individuals. The fragility of this admirable enterprise has been highlighted by numerous jurists, including Vico and Montesquieu. It is based on individuals’ ability to renounce all consideration of their personal interests in discussions of the public interest. Montesquieu described this political virtue as ‘a renunciation of the self, which is never pleasant’.

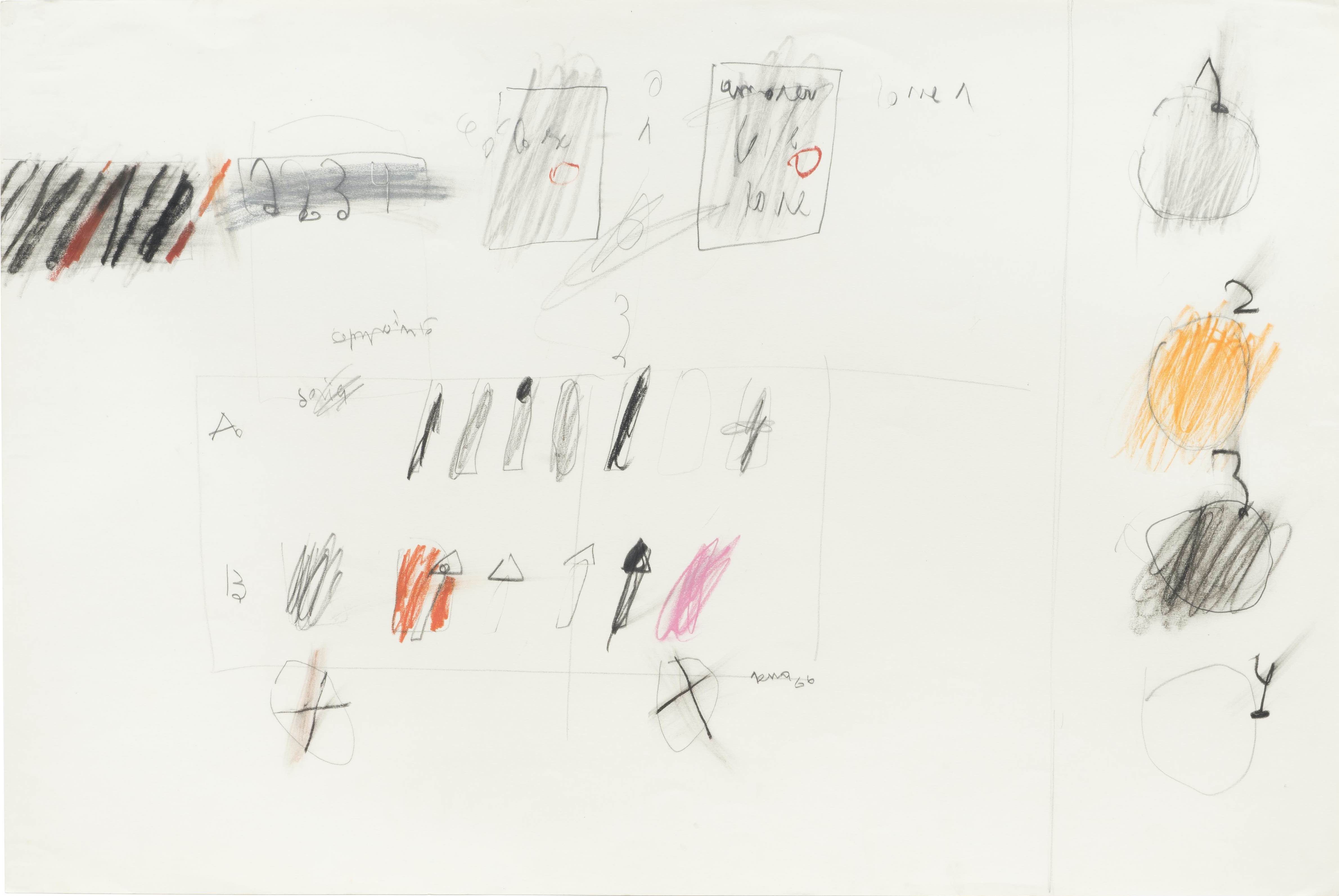

António Sena, Untitled, 1966 © Photo: João Neves

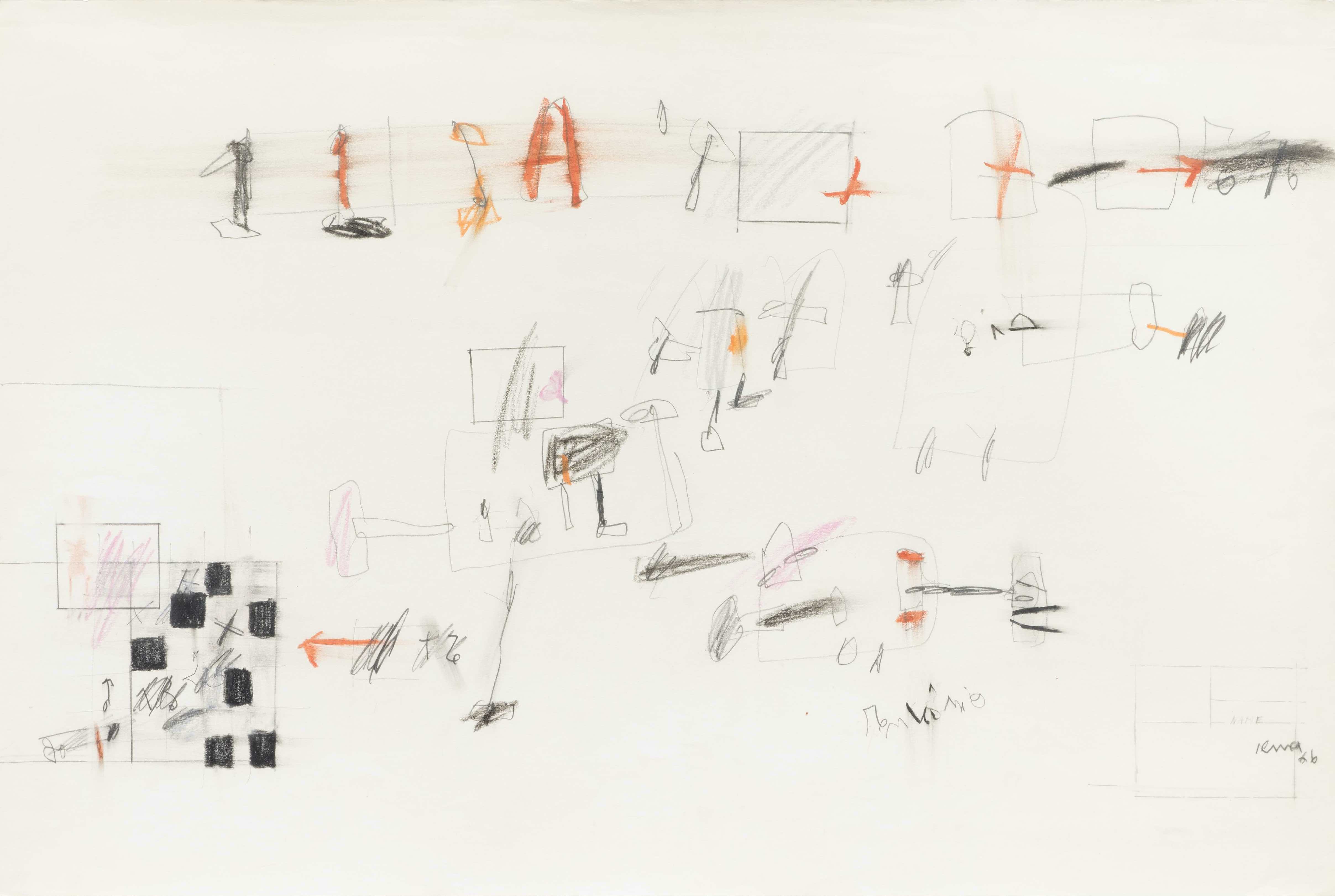

António Sena, Untitled, 1966 © Photo: João Neves

"In the present day, the ideal of the rule of law is countered by that of governance by numbers, which is linked to the current digital revolution but is rooted much further back in history."

In the present day, the ideal of the rule of law is countered by that of governance by numbers, which is linked to the current digital revolution but is rooted much further back in history. The dream of harmony through calculation can be traced back to Pythagoras and, more recently, to the Galilean revolution and its mathematical representation of the universe. The idea that God recorded the laws governing nature using figures rather than letters has taken hold. When the laws dictated by this mathematician God are deciphered, they point to the possibility of becoming, as Descartes put it, ‘master and possessor of nature’.

Quantification was quickly extended to ‘social phenomena’ on clearly normative grounds, as the work of Lorraine Daston and Alain Desrosières sets out. Society was approached as an object that could be observed and measured to ascertain the laws governing it, as if they could be formalised mathematically like the laws of physics. This unit of mathematical, physical and legal thought occupies a central position in Leibniz’s great work. The generic concept of ‘society’ did not emerge until this time but it quickly took hold in areas ranging from the ‘social contract’ to ‘socialism’ and ‘social security’. A whole branch of science developed around it: sociology. This led to attempts to ground the law in calculations of probability based on observing society. A public health issue appears to have prompted the first debate regarding the legitimacy of this new art of governing: whether or not inoculation against smallpox should be compulsory. By obliging the population to accept the vaccine, the disease would be thwarted but some inoculated people would die. Most of the ‘enlightened’ thinkers of the time believed that progress could only be achieved by using scientific data as the foundation for human governance. The only philosopher to oppose this widespread opinion and demonstrate that human problems could not be resolved through calculations based on imperfect data was d’Alembert. This early manifestation of the ‘social sciences’ gave rise to unequivocal, important progress in knowledge. However, it also triggered what Renan described as ‘the audacious but legitimate pretension to organise society scientifically’.

[...]

Share article