On Affective Resonance – Ângela Ferreira’s Creative Research

Ângela Ferreira was a pioneer in bringing to contemporary art topics and themes that are now omnipresent and are driving cultural debate. Having spent over thirty years researching the colonial past, the postcolonial present and the future on the horizon, her art has a consistency and coherence that has achieved national and international recognition. In this issue of Electra, Ângela Ferreira presents paintings made for future memories, based on murals shown at previous exhibitions. In the introductory essay for this portfolio, the curator and art historian Nomusa Makhubu writes, ʻI am drawn to the affective Ângela Ferreira Pan African Unity Mural I-X resonance enlivened by interlaced narratives [...in the Pan African Unity Mural...] re-sounding histories of exile, loss, struggle and defiance [...and also of optimism and hope...]. It is akin to what Tina Campt calls “affective frequencies”. To see what we don’t see, to pay attention to the resonances between each image and object, is to experience how “sublimely quiet images enunciate an aspirational politics”ʼ. The images that Ângela Ferreira shows here are thus a place in which visibility, inclusion and centrality are restored to those who have long inhabited the invisible peripheries of amnesia, exclusion and ignorance.

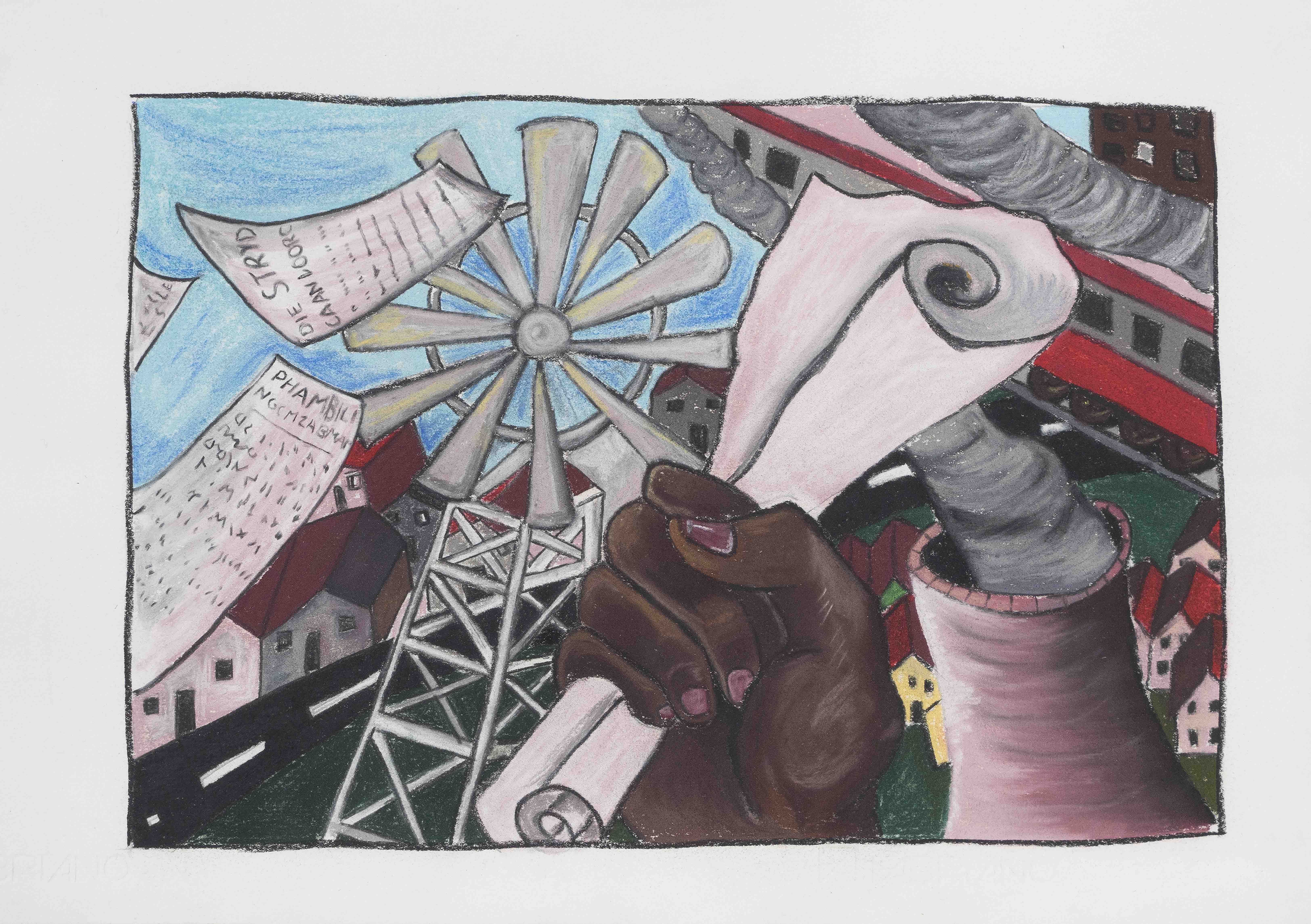

Ângela Ferreira

Pan African Unity Mural VIII, 2019

Dry pastel on Fabriano paper

35 × 50 cm

In the collection of Fundação Luso- Americana para o Desenvolvimento in deposit at Fundação de Serralves, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto

© Photo: João Neves

In the opening of her biography, Miriam Makeba wrote,

I look at a stream and I see myself: a native South African, flowing irresistibly over hard obstacles until they become smooth, and, one day, disappear – flowing from an origin that has been forgotten toward an end that will never be.1

Makeba was not bridled by a narrow sense of national belonging, restrained by a suffocating and covetous accumulation of property, or tied to captive labour on captured land. Her ‘flow’, if one were to take the metaphor literally, smoothed over charted, partitioned, fenced, scorched and sapped landscapes, like water transforming jagged rocks into pebbles. Intimating Makeba’s self-sacrificial advocacy against racism, this metaphor diffuses definitive origins and destinations, defying the tyrannical imperial organisation of space. To see oneself as a flowing stream with no immediately discernible origin nor destination, is as if to say, ‘things never settle, and they should not’. In this way, physical sites that may seem static are infinite flows of unsettled converging resonant narratives produced through relations and connections between people. It is this sense that spaces are not just inhabited but created, lived and felt, that underpins Ângela Ferreira’s oeuvre.

Spanning over three decades of practice-based research, Ferreira’s work homes in on specific sites, drawing out lived experiences that connect people and places. Although trained as a sculptor, the focus is not so much on the object but on the spatial relations between objects, ideas and stories. It sets in motion the navigation of multiple places, creating environments in which one can feel the volatility of power in the production of spaces.2Pan African Unity Mural (2018) can be considered an introspective confluence of previous and current research on specific incidents and personalities. Reflecting on her work, I am drawn to the affective resonance enlivened by interlaced narratives. Buildings, homes, towers and other sites reverberate like songs, re-sounding histories of exile, loss, struggle and defiance.

Take for example the villa offered to Makeba by Sekou Toure in 1967 in Dalaba, Guinea-Conakry, where she lived while exiled from South Africa and alienated in the USA. In Ferreira’s illustrations, Makeba’s villa is hoisted onto cables running from one site to another as if it were movable and could be translocated to other places, like a prompt that home is not confined only to a physical house but that the memory of specific sites we call home can move with us. I am reminded of a documentary that depicts Makeba moving through the house, looking at the patterned floor and ceiling, while singing and recalling home. This was the significance of Dalaba: the resonance Makeba felt with the pained South African landscape to which she could not return. Yet Dalaba affirmed her defiance and the exigency of African independence. Unlike in South Africa, for the Guineans ‘whatever they are standing on is theirs, it’s their land’.3 Dalaba is also where Makeba lost her daughter, Bongi, and grandson. The house signals the arduous transitions of African independence – it is a place that represents many other places and encounters. After all, Makeba, or Mother Africa as she was affectionately known, was a citizen of many countries and symbolised pan African solidarity. Like a reflection, this resonance is felt when looking at the illustration of the house that was Ferreira’s home in Maputo. It is also hoisted up,evoking the spectres of colonialism in architectural styles and settler colonial unsettled notions of home, marking such territorial concepts as native, foreigner, settler – generations thrust into social situations that concretise difference. But one is moved to look in and through this in order to hear and unravel the resonances we do not immediately feel: what is imagined when we think of the essence of homes: families, communities, kinships, sometimes straddling visible and invisible borders.

The cables that hold up buildings intersect in the physical reproduction of the tower that is referenced in the Pan American Unity Mural, a fresco completed in 1940 by the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, the African-American artist, Thelma Johnson Streat, and others. The tower, like all the engineering mechanisms that alter and transmute place, is a point of convergence between man and machine in a conceding landscape. Although dams are signifiers of modern progress, Shasta dam in California, which was constructed using cranes controlled through a tower like this, was built on land from which indigenous communities were forcibly removed. It conceals burial sites and the lives that were lived there. What can be felt is the tension in the muted noise of destructive construction, extractive labour and displaced families.

This troubled depiction of labour and displaced families is echoed in the reproduction of the Community Arts Project (CAP) mural at Community House in Salt River, Cape Town. This mural is the basis of the ten pastel drawings resulting from Ferreira’s Pan African Unity Mural. In it, I am captivated by the image of the train on its descending railway track, perforating the congested landscape. It is reminiscent of Hugh Masekela’s 1974 composition, Stimela, in which he says:

There is a train that comes from Namibia and Malawi,

There is a train that comes from Zambia and Zimbabwe,

There is a train that comes from Angola and Mozambique,

From Lesotho, from Botswana, from Swaziland,

From all the hinterland of Southern and Central Africa.

This train carries young and old, African men

Who are conscripted to come and work on contract

In the golden mineral mines of Johannesburg

And its surrounding metropolis, sixteen hours or more a day

For almost no pay.4

Deep, deep, deep down in the belly of the earth

When they are digging and drilling that shiny mighty evasive stone

[…]

Or when they sit in their stinking, funky, filthy

Flea-ridden barracks and hostels

They think about the loved ones they may never see again

Because they might have already been forcibly removed

From where they last left them

Or wantonly murdered in the dead of night

By roving, marauding gangs of no particular origin

We are told

They think about their lands, and their herds

That were taken away from them

Masekela’s taunting voice condemning the brutalities of extractivsm and the migrant labour system that crosses over geographical boundaries, echoes over time. In the mural, as the railway track slopes, workers are joining tools to unite. It is through this unity that they are re-connected to their families from whom they are separated: a child connects these tools to a pencil held by a mother carrying wood on her head. The imparting of knowledge portrayed in the mural ‘sparks’ youth rebellion for workers’ solidarity. A young person reads a book with the slogan ‘Freedom or Death, Victory is Certain’which is associated with posters and badges of the South African Youth Congress (SAYCO) and the Cape Youth Congress (CAYCO). These posters paid homage to the youth protests of 16 June 1976 against the apartheid government’s inferior education for Black people, Bantu education. In the mural, images of workers carrying Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and United Democratic Front (UDF) pamphlets are portrayed in a landscape of hostels, factories, cooling towers, mines, shacks and confining township houses – the legacy of a regime that usurped space for control and accumulation. The mural evokes the Marxist slogan, ‘proletarians of all countries, unite!’ and ‘workers of the world unite!’ contending that transnational Pan-African solidarity is crucial for workers against global, cross-border capitalism.

Pan African Unity Mural places into proximity a number of sites, flowing between Cape Town, Maputo, California, Boston, Algiers, Conakry and others. Movement is central in this installation, a space-time convergence of many narratives in one space. It defines modern politics, where power is the capacity to control the relationship people have to space and their movement in it whether forced or voluntary, and whether it is colonial territorialisation, settler occupation and the transplantation of infrastructure and architectural styles from the colonising country, segregation, land appropriation, privatisation, or reclamation.

For a fugitive like Jorge dos Santos, originally named George Wright, movement in his life story reflects the brutality of structural racism that deprives people, corralling them into a carceral labour-binding system. Wright was sentenced to three decades after murdering a person for $1.25 for a bus fare that he needed after his wallet was stolen. This turn in his otherwise ordinary life triggered a lifetime of being a fugitive across different geographical spaces: from the USA to Algeria, France, Guinea-Bissau and Portugal. It is of significance that in Pan African Unity Mural this contingent movement is represented through the DC-8 Delta airplane that Wright, along with others, hijacked in 1972. The plane, symbolising being in-transit, is simultaneously a site of the crime as well as a point of escape to Algeria to join members of the Black Panther Movement who were exiled there, and eventually to a life lived under the radar in Portugal. Unlike the train that epitomises the migrant labour system (and Cecil John Rhodes’ Cape-to-Cairo imperial fantasy), the airplane signals the contradictions of globalisation – the space-time compression that shrouds the crimes of capitalism. Wright’s narrative is fascinating precisely because it points to the extraordinary individual lives that claim the right of a full life despite the limitations posed by oppressive spatial politics.

For each component in Pan African Unity Mural there is a resonance of affect: the undercurrent of loss, strife, tragedy, and also optimism and hope. It is akin to what Tina Campt calls affective frequencies. To see what we don’t see, to pay attention to the resonances between each image and object, is to experience how ‘sublimely quiet images enunciate an aspirational politics’.5 Many lives converge in this space: the workers’, Makeba’s, dos Santos’, Ferreira’s and many other invisible lives. Within it, the ‘flow over hard obstacles’, the resistance against hard, dividing edges that is channelled in narratives, points to the salience of relationality and the need to find, hear and feel the unexpected.

Share article