1.

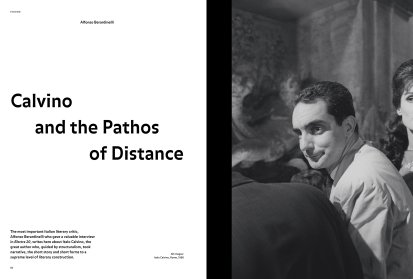

The most important Italian literary critic, Alfonso Berardinelli who gave a valuable interview in Electra 20, writes here about Italo Calvino, the great author who, guided by structuralism, took narrative, the short story and short forms to a supreme level of literary construction.

Italo Calvino, 1960 © Photo: Scala, Florence / Luce Cinecittà, Rome

It is hard to imagine a more fortunate and successful literary destiny than that of Italo Calvino. He is undoubtedly the best-loved and most popular author among Italians of all ages. Read in schools, studied in universities, analysed and admired unreservedly by critics, Calvino accompanies us from childhood to old age. In him, after all, there has always been both puer and senex, both play and distance from the world. Calvino has come to take on the role of pedagogue and moralist to the children and young people of today’s middle class.

Having started out as a political activist in his youth and becoming a storyteller of certain episodes of the resistance to Nazi-Fascism in the style of fables, capable of writing tales of surprising clarity and rhythm, Calvino later became the most sophisticated self-reflexive storyteller that Italy has ever known.

The years of his maturity were as doubtful and perplexing as ever. His intelli- gence, by then labyrinthine and saturnine, bored with Italian social and political reality, drove him to a determined escape. The escape route was Paris, the centre of the European literary scene, from which, in the 1960s, theoretical news about language in general and literary language in particular was constantly arriving. Although it did not seem that Paris was then very interested in the art of storytelling, nevertheless ‘structural analysis of the short story’ was methodically, even obsessively practised. Fleeing from an Italy convinced it was on the threshold of a radical ‘political transition’ (which would instead only give birth to the ‘anarchic Stalinism’ of terrorist groups), Calvino increased his passion for distance and for ‘looking in from outside.’ His fiction thus became the expression of a Cartesian misanthropic instinct that drew him irresistibly towards structuralism. His problem or challenge was to narrate by theorising, or to theorise in the form of narrative.

“From the outset, Calvino was a storyteller who distrusted the novel. Social and moral problems and the study of everyday life as micro-history never formed part of his focus.”

After all, observation of nature (his father was a botanist) and a love of fable as vehicles of wisdom had always been two ways for him to keep ideologies and social reality at a distance. From the outset, Calvino was a storyteller who distrusted the novel. Social and moral problems and the study of everyday life as micro-history never formed part of his focus. The only exception to this was the most anomalous but perhaps best of his books, The Watcher, published in 1963, when Calvino was in his forties and the commitment to realism was still a strong moral temptation in Italy. The decade of the new workers’ struggles, the New Left, and the Protests of 1968 had just begun. Liberation from ideological boredom and the duties of politics, whether true or false, was not yet on Calvino’s agenda, however. If he mistrusted literary realism, Calvino had also avoided the spirit of the avant-garde, whose literature sought to be inaccessible to the majority of readers. The Gruppo 63 had chosen to pursue avant-garde literature for an audience of literature professors. Calvino, on the other hand, wanted to be a writer ‘for everyone,’ even when his narrative writing presupposed a narratological theory of myth and fantasy.

The narratology that appealed to Calvino was one that favoured the short story and short forms, not the novel, which from Balzac and Dostoevsky to Svevo, Proust, Mann and Musil required a substantial amount of material. Calvino, in contrast, worked by lightening the narrative material. His characters are distant figurines, snappy monochrome two-dimensional profiles that give movement to the narrative.

Such stylisation naturally contains its own ‘morality of form’. Despite the appearance of lightness and the childlike smile, Calvino is in fact a moralist who fights against what he judges to be the heaviness and slowness of morality. He seeks to keep fears, anxieties and paralysing doubts at bay. His ideal is order. Even when it is a complex order that defies chaos, his agenda is mental hygiene.

“Despite the appearance of lightness and the childlike smile, Calvino is in fact a moralist who fights against what he judges to be the heaviness and slowness of morality.”

2.

All of Calvino’s fiction can be read as a well-organised and cunning strategy to reject the novel, a literary genre that was awkward and too challenging for Calvino. In the Note accompanying the one-volume collection of the trilogy Our Ancestors, from 1960, the author makes a confession: ‘I am not interested in psychology, the inner self, interiors, family, custom, society.’

For Calvino, 1945 was a ‘year zero,’ a kind of end of history set in the cruel and dynamic scenarios of a partisan civil war. A war of the young and very young, an epic of origins, a fable of the discovery of the world through the eyes of a boy, while the body is in motion, in the open air, at a moment when the old society no longer exists and a new society has not yet come into being. At such a juncture, the only community solidarity is that of a group of young fighters. For Calvino, 1945 was not only the end of the first half of the 20th century, but also the end of everything that still tied the 20th century to the 19th, the century of the novel. In such a fable of the world beginning anew, the only ‘moral of the fable’ is that life wins by rejecting the fear of life, laughter wins over tears, movement over the inertia of habit.

[...]

Share article